As anyone who takes notice of the natural world knows, nothing stays the same. I visit my local beaches around East Looe so frequently that I know every rock and every pool. Yet, the more time I spend here, the more I notice.

Sometimes I learn something new about a familiar animal, sometimes I am treated to fascinating displays of natural behaviour, and sometimes I find species I never seen before. Here are five recent highlights from my local beach.

Cushion Star Hatchlings

It took me many years to realise that cushion stars lay eggs and to finally see my first just-hatched babies. Now I know what to look for, I see their eggs everywhere in the summer rock pools.

I find a cluster of new, tiny cushion stars and fall in love with their bright orange perfection and impossibly small tube feet.

A Hermit Crab Without a Shell

The thing that everyone knows about hermit crabs is that they live in the empty shell of a sea snail. It’s not entirely true to say that they have no shell of their own though. Hermit crabs have tough claws and shell covering the front part of their body. Just like other crustaceans, they moult their shell each time they grow.

Hermit crabs don’t, however, have a shell on their rear end. Instead, they have a long, spiral tail, which is soft and bendy. When the hermit crab finds a suitable shell to live in, it winds its tail up through the internal structure of the shell, clamping its home in place.

If a hermit crab loses its shell to another crab or a predator, it finds itself in a real predicament. That soft tail is vulnerable to attack.

When Junior and I come across a homeless hermit, we locate a suitable empty shell and watch what the crab does.

The whole process is astonishingly quick.

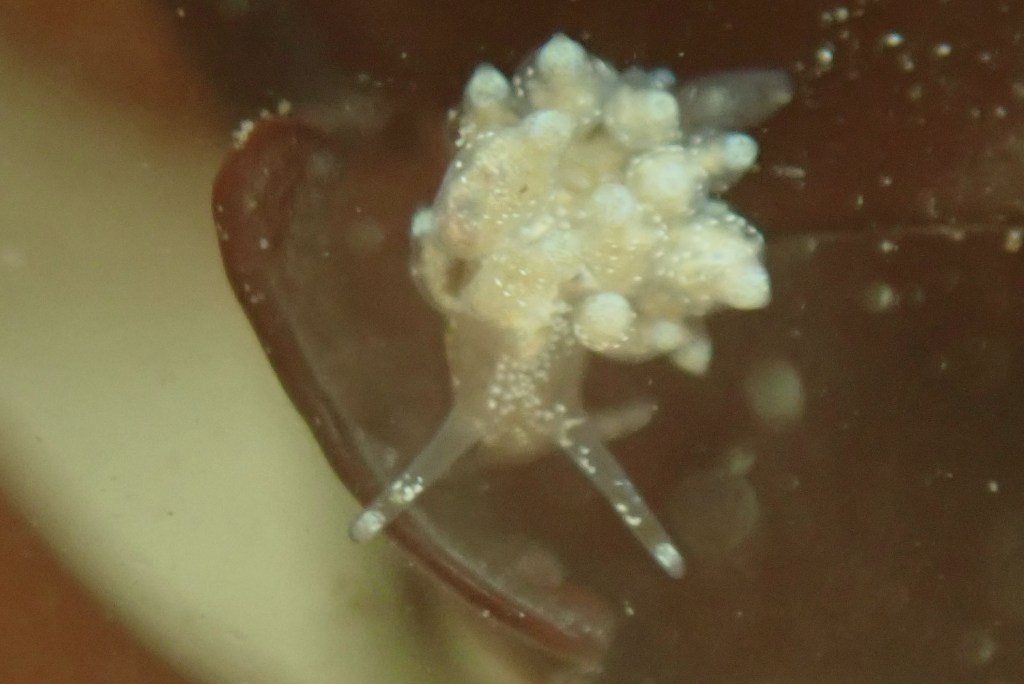

Nudibranch Sea Slug – Eubranchus exiguus

Regular readers will be well aware of my (entirely justified) obsession with sea slugs. If you aren’t already aware of how exquisite these little animals are, you might like my introductory talk for The Shores of South Devon.

Most UK sea slugs are small and some are so tiny that you can barely see them with the naked eye. I spot a speck of jelly on some seaweed and spend the next twenty minutes crouching in the water to try to focus my camera on it.

The slug is moving, the seaweed is moving and my hands are far from steady, but the photos are good enough. Meet a species of nudibranch sea slug that is new to me: Eubranchus exiguus.

The long, inflated cerata on the back of this sea slug look like they have been pinched in near the top, giving them a vase-like shape. Scattered white flecks adorn its body. When I can get it in focus, it is a fabulous-looking creature.

Rock Goby Eggs

There are few things more mesmerising than fish eggs. They are generally transparent, meaning that you can see the babies’ eyes looking out at you. As the fish grow, they become fidgety, twisting and turning inside the egg. Rock gobies are a very common rock pool fish and their distinctive capsule-shaped eggs are usually well-guarded by the father, who stays close until they hatch.

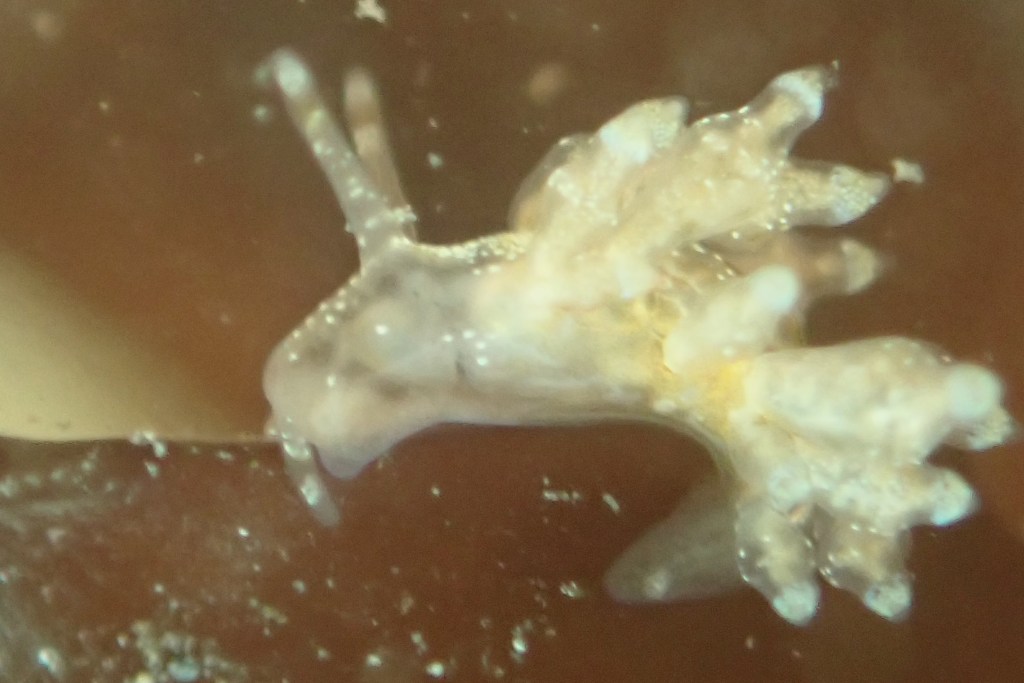

Doto slugs (and a bonus slug)

Finding sea creatures in the pools is a haphazard business; you can rarely be sure of finding even common species. However, if I want to find a Doto sp. slug, I know just where to look.

In places around my local rocks, the brown seaweeds (wracks) are so completely covered in hydroids that they look like they have grown beards. Very close-up, these hydroids (Dynamena pumila) look like stacks of pale triangles. Among them, feeding on the hydroids, are the tiniest splodges of jelly – the Doto slugs.

Out of the water, they are a sorry, squidgy mess. If, however, I can persuade one off the hydroid, I can put it in the water to reveal its towering jelly-mould structure decorated with charming crimson or black dots. The satellite dish rhinophores (antennae) on the slug’s head are an impressive accessory too.

Whether they remind you of cakes or jellies, there’s something gloriously edible-looking about the Doto slugs.

Warning: Slugs are not dessert. Don’t eat rock pool wildlife.

It isn’t clear what species these slugs are; Doto slugs are notoriously difficult to identify. They were initially thought to be Doto coronata. That species isn’t now believed to feed on Dynamena pumila, so they may be a species known as Doto onusta – or something else. Whatever they are, I absolutely love to see them.

And now for a bonus slug… The orange-clubbed slug, Limacia clavigera, is a frequent find, but is too fabulous to be left out. Enjoy!

Have you found anything new on your local beaches? I love to hear what other people have seen and can often help to identify unusual finds if you’d like to get in touch.

You can also find identification guides to some common rock pool creatures such as crabs, starfish and fish on my Wildlife page.

Whatever the weather, always stay safe in the rock pools. Follow my rockpooling tips to look after yourself and the wildlife on the shore.

This website is a labour of much love and the content is available for free to everyone. My wonderful readers often ask if there is a way to support my work. You can now ‘buy me a coffee’ through my Ko-fi.uk page. (Just click donate and you can set the amount to pay by PayPal). Thank you!