Back in March, Junior and I had the opportunity, together with our fabulous home education group, to explore the shore in Looe on one of the lowest tides of the year. For these keen rock poolers, searching for rainbow slugs was the perfect challenge.

“So, what does a rainbow sea slug look like?” asks one of the children. A good question.

I admit I have never seen one in real life.

“It’s tiny, so you’ll have to look closely,” I say. “Maybe the length of my little fingernail?”

I hold my fingernail out for inspection and the group gathers round.

“If you find this slug, you’ll know,” I assure them. “It might be tiny, but it’s a fluffy rainbow, with the brightest colours.”

Since the first UK sighting off the Isles of Scilly in 2002, the rainbow sea slug, Babakina anadoni, has been found increasingly frequently, including in several locations around Cornwall. Needless to say, I have been looking for it. Everywhere. Endlessly.

The general view is that this species feeds on hydroids, in particular the rather odd looking (and giggle-inducing) Candalabrum cocksii.

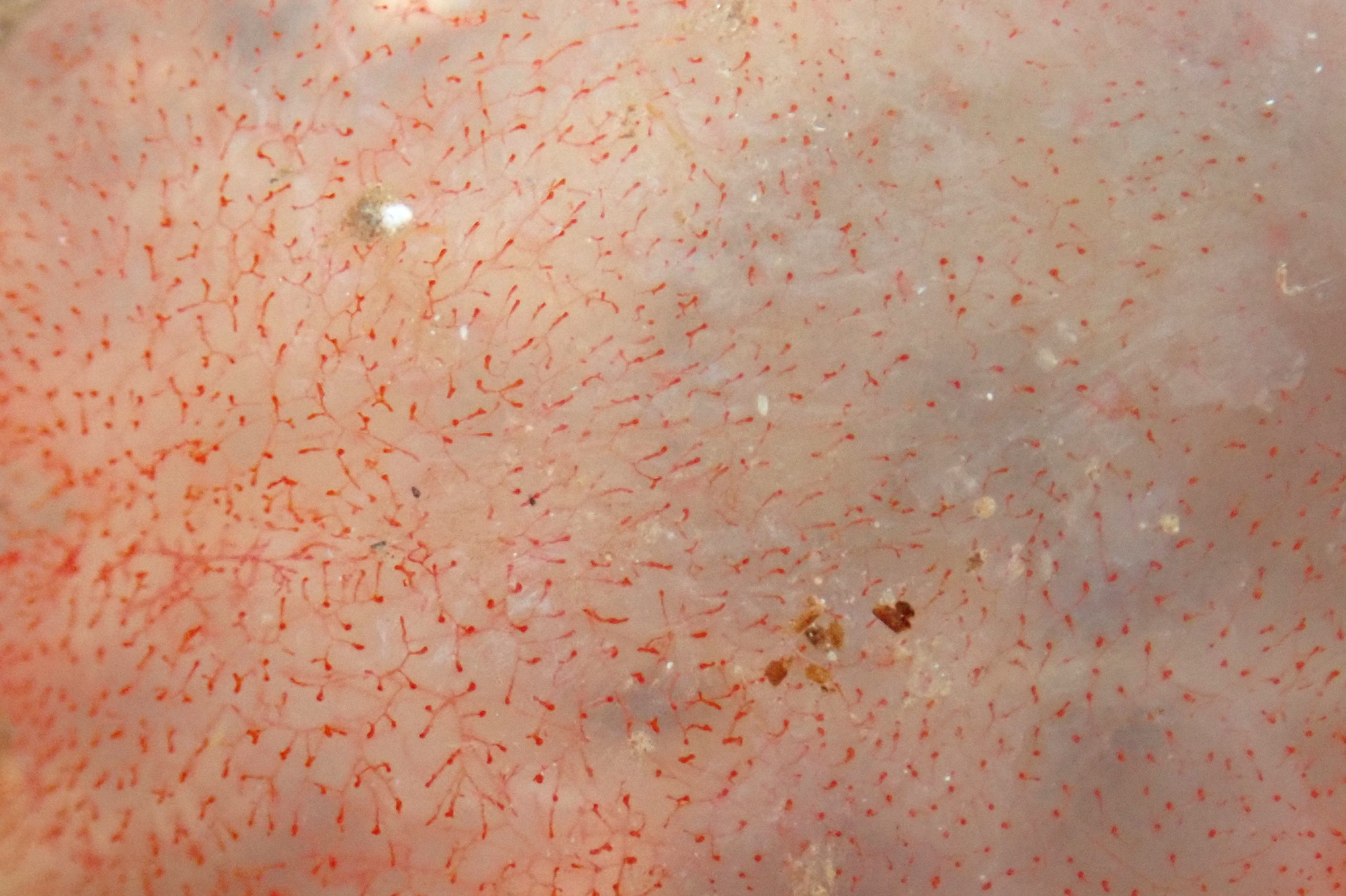

Most hydroids live in delicate, feathery colonies. Described by the naturalist Cocks 1854 (and previously by Gosse in 1853), Candelabrum cocksii looks more like a blobby worm and, to complete the look, it can even wriggle vigorously.

You can just about see why Cocks compared this little animal to a candle-holder. The main, burgundy-red body of the animal often sticks upright like a candle, with the animal’s mouth at the top, and seems to be propped in place by its rounded base, comprising many tiny white balls, and frilled tentacles. Hydroids use stinging cells in their tentacles to fire paralysing toxins into passing prey in the same way as other cnidarians like anemones and jellyfish.

Underneath the base is a “foot”, which secures the animal to the rock, but can also extend when it wants to move. In fact, the whole animal is highly extendable and transforms in appearance when it puts out its short, round-ended tentacles.

To make itself seem even longer, it can also connect to other Candelabrum cocksii, forming a pseudo-colony.

To my mind, lots of Candalabrum cocksii hydroids should equal lots of well-fed rainbow sea slugs. Sadly, as so often happens, the slugs don’t seem to have read the same articles as me. After many months of looking, I still haven’t found one.

Fortunately, Junior’s home education group have good form. We have set out several times with a particular mission, most recently to find baby sharks . Each time, they succeed. Therefore, today we are going to find a rainbow slug.

Conditions on the shore are beautiful. For once, we have sunshine, very light winds and a calm sea. Not only that, but there is a perfect spring low tide forecast. We follow the retreating sea towards an emerging rocky reef, checking everywhere along the way.

There are lots of fabulous crabs, fish, squat lobsters, anemones and more, but no rainbow slugs.

As low tide approaches, I am delighted to bump into the legendary (and also very real) Dr Keith Hiscock of the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, who is enjoying his own marine explorations. We catch up briefly before I am called away to see another exciting find by the children: a catshark egg case that appears to be on the brink of hatching.

I keep up my increasingly frantic search for a rainbow sea slug without success. There’s a little Jorunna tomentosa slug and a beautiful red Rostanga rubra. I’m also happy to see a young snake pipefish, but there’s no sign of rainbow slugs.

I am taking some photos of a gorgeous little Anapagurus hyndmanni hermit crab, when Junior calls over to say that Keith found a rainbow slug. For a moment I think he’s pulling my leg, but Junior knows that slugs are a serious matter.

“He found it earlier,” he says. “Over there somewhere.” He points to the opposite side of the lagoon.

My heart leaps and sinks at the same time. There’s a rainbow slug! However, it’s unlikely to be more than 2cm long and is somewhere among many square metres of rocks and seaweed.

I slosh through the water to where Keith is exploring and he tells me he has marked the place. Fantastic! I call the kids over and, together, we start hunting for a rock marked with a piece of kelp.

Inevitably, the tide is already turning and time is against us. We find one rock with kelp on it and search all around to no avail. Then we try another place. Nothing.

Keith to the rescue! With a little hunting around (rocks and kelp are incredibly plentiful on this part of the shore), he identifies the right area. The first rock we gently turn is slug free and we place it back, glancing nervously at the edge of the sea, which is visibly flowing in our direction.

When we turn the second rock, the children gasp in excitement. Yes, it’s small, but there is nothing disappointing about this slug. The pinks, purples and yellows are virtually glowing.

“It’s like a Pokémon!”

The children have a point. With its bright pink headgear and multicoloured mane of cerata along its back, this creature would not look out of place on a trading card.

Vivid colours like this often announce to any would-be predators that an animal is toxic. Many sea slugs retain toxins from their food, or even stinging cells, which they keep in their cerata (the sticky-up bits on their backs). My books neither confirm nor deny that Babakina anadoni does this, but I imagine that few creatures would be foolish enough to chance a bite.

Excitingly for me, the rainbow slug is not at all camera shy. It keeps changing its pose on the rock, allowing us to take some excellent shots from all of its best sides.

Amid the appreciative chatter and my own delighted squeals, I do my best to do justice to this slug’s stunning appearance.

Also on the rock is a Candelabrum cocksii hydroid – possibly slightly chewed by the slug.

I cannot thank Keith enough for sharing his discovery with us all. What an incredible experience for all of us. There may well be some budding marine biologists among the group!

With the tide pushing at our heels, we retreat to the top of the shore to relax and eat a celebratory ice cream, still buzzing about the beautiful slug and its amazing colours.

The intertidal rocky shore is a fragile environment that we can all help to protect. If you are heading out to look at the wildlife, join a local expert-led event if possible and be sure to follow my rock pooling tips to help you to look after the wildlife and stay safe.

This website is a labour of much love and the content is available for free to everyone. My wonderful readers often ask if there is a way to support my work. You can now ‘buy me a coffee’ through my Ko-fi.uk page. (Just click donate and you can set the amount to pay by PayPal). Thank you!