We are into the second month of 2026 and I feel sure we have yet to make it through a whole day without rain. As someone who would happily hibernate through the post-solstice months of endless winter, I find this season especially grim when conditions are too stormy to safely rock pool.

Friends are reporting similar things. Between financial pressures, winter illnesses, and certain world leaders who, to use my favourite German saying, “don’t have all their cups in the cupboard”*, people are understandably feeling that the darkness is more pervasive than usual.

My favourite way through the gloom and drizzle is to look for “glimmers”. It’s an actual thing apparently, based on Polyvagal Theory. We won’t debate the science of that here, but I like the word “glimmer” and going on a glimmer hunt feels good.

The idea is to take a moment to notice and appreciate the tiny positive things around us, whether that’s an actual glimmer of light breaking through the clouds or – more likely – the flicker and sparkle of a water droplet, the sound of a bird’s wings or a falling piece of sea foam.

When we stop to notice the little things, it can distract us from the gloom, lift our spirits and help us to refocus. Glimmers are things that make the world feel safer. They are, therefore, just what we need right now.

With this in mind, I pile on the waterproofs and scramble down to my local rock pools with my trusty camera. Here are my glimmers: the beautiful, the intriguing and the frankly bizarre things that I find to distract me from the fact my hands are numb with cold.

The world can feel heavy sometimes, so come with me into the rock pools, dip into my photos and know that pancake day is right around the corner!

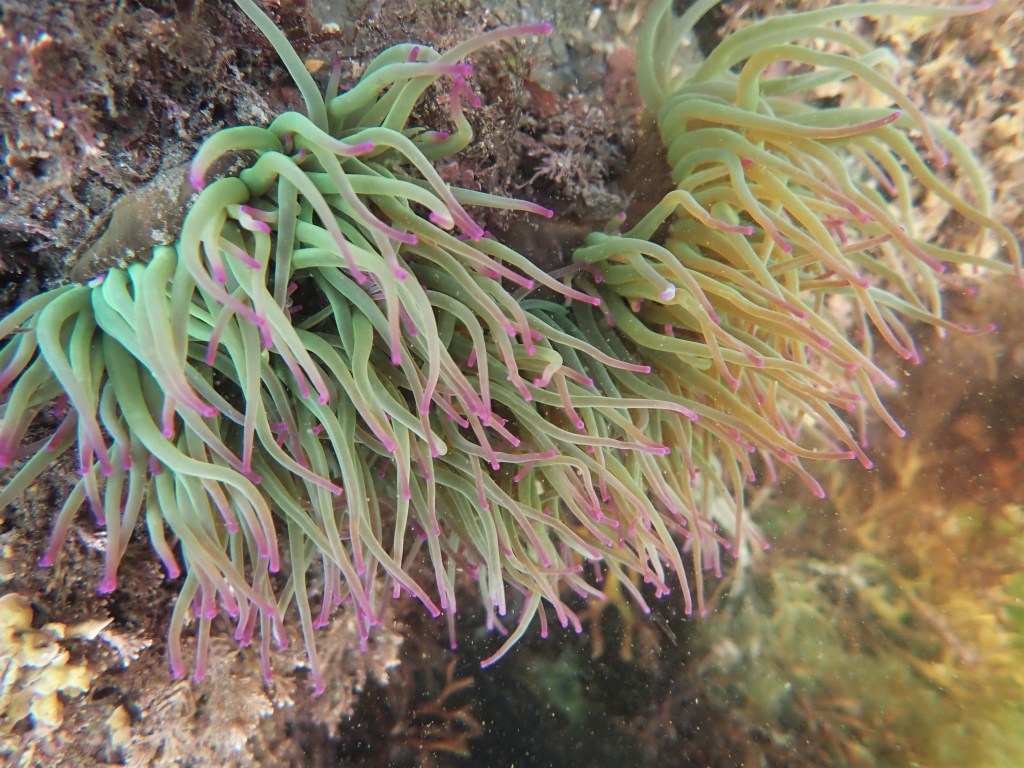

Among the greyness of the season, these vivid green snakelocks anemones against a pink-algae clad rock stop me in my tracks. They remind me of making tiny gardens in a tub as a child, full of bright mosses and petals.

In the absence of blue skies, this gorgeous patch of blue sponge (Terpios gelatinosa) will do nicely. The deep velvety colour is soft and comforting.

The real stars may be mostly hidden behind clouds, but this star ascidian is a reminder of the clear nights that are coming. Under my camera, I can see the siphons opening and closing, filtering water.

Glimpses into these animals’ worlds are mesmerising and such a privilege. When I Iook out over the sea, I always think of all these amazing animals, living their lives, unaware of anything beyond their realm. Somehow, it puts things in perspective.

The things I don’t understand are some of my favourite glimmers. Something as tiny and light as a sea spider with its frail twig-like body should surely not be able to survive the storms on the rocky shore? And yet here he is, not only surviving but carrying a clutch of eggs under his abdomen. In these animals, the males carry the eggs.

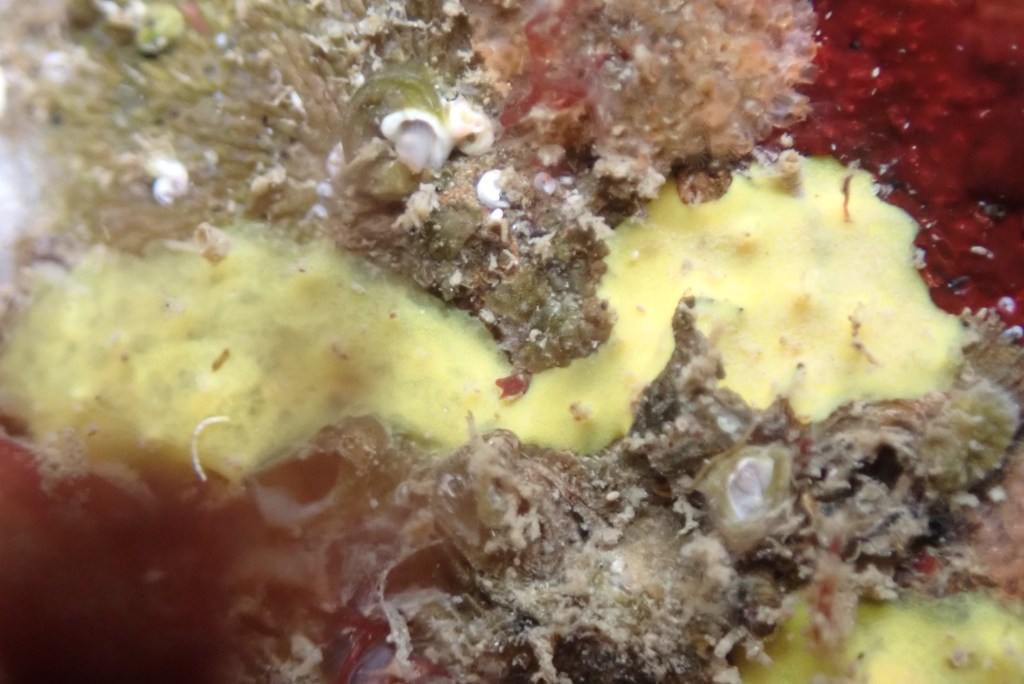

Sea slugs light my world, so the lemon-yellow glow of a Berthella plumula is sure to lift my spirits.

I also find a smart little white-ruffed slug (Aeolidiella alderi) and, after much determined staring at sponges, a Doris ocelligera. It looks so much like its prey that I have to watch it for several minutes until it extends its tall rhinophores and fluffy gills to be sure it really is a slug.

As the tide starts to rise, the waves surge ominously near to where I am standing. I look under one last rock and notice a dark shape around the size of my palm. In the silty water, it is far from clear but I put the camera in the water to take some shots of what I am sure is a baby topknot.

These gorgeous flatfish specialise in hiding on rocky shores by changing their colour to blend in and by suckering onto the underside of the rocks. This youngster already has these tricks perfected.

A few seconds later, the little topknot slips off the rock and undulates away into the seaweed. I realise I am holding my breath in appreciation.

My final glimmer before leaving the shore is the other-worldly bubbling cry of a curlew somewhere in the mist. I look all around and see nothing. Still, knowing it’s there is enough, just as I know there will be sunnier days ahead. Not many – this is Cornwall after all – but even here, the rain will pause eventually.

* In German: “Nicht alle Tassen im Schrank haben.” One to learn for your next holiday.