With our bingo cards of southerly species part-filled after an exciting day on the south coast, our visitors from Wales still had quite a wish list left to accomplish. To find cup corals and Celtic sea slugs, a trip to a more exposed coast would be needed. Naturally, I suggested my favourite beach: Porth Mear.

The weather was on our side, taking a break between the endless storms that have characterised the summer holidays. So, with swimmers and beach shoes at the ready, we walked down a valley alive with tortoiseshell butterflies to where the bluest sky met the bluest sea. Even the pools at the top of the beach churned with trapped young mullet, scurrying shore crabs and bright anemones. While one of our friends stayed looking at the upper shore pools and gathering shells, Junior and I led our other friend on a long slip and slide across the rocks to reach our goal.

With two hours to go until low tide, we could safely allow ourselves a few distractions on the way. I couldn’t resist stopping to take photos of this wonderful Montagu’s blenny, which let me creep ever closer with my camera as it sheltered under a limpet shell. Blennies are able to move their eyes independently and this one kept an eye on me while scanning the surface of the pool with the other.

My friend was delighted. Although it hadn’t appeared on our bingo card, the Montagu’s blenny is another southerly species which he had never seen in North Wales. This was too easy!

We had met some St Piran’s hermit crabs at Hannafore the previous day, but the colony here was well worth a look too. We found scores of these crabs in and around the pools along a couple of rocky overhangs, living in a range of sizes of shell. This species is doing well here, towards the northerly limit of its known range.

The painted top shells on this beach are always especially pink and beautiful, perhaps because in this more exposed location, they tend to accumulate less silt and micro-algae on their shells. We stopped to take plenty of photos.

Although it can be hard to find stalked jellyfish in the summer when the beach is thick with the seaweeds they attach to, we were determined to tick one or two off the list, especially Haliclystus octoradiatus. This may not be a particularly southerly species, but it occurs frequently around Cornish coasts. After much searching we found a very small blob that was probably a juvenile, but I could only confirm that by looking at photos afterwards.

As the tide dropped further, we picked up our pace and clambered towards a wave-battered gully. This area is only accessible on the lowest tides and, even then, is often out-of-bounds due to the huge swells that pound these rocks for much of the year. Today, the calm conditions were perfect and we could explore in relative safety while keeping an eye on the time.

Junior made straight for the high rocks, where he quickly found the first Celtic sea slug, out in the open among the barnacles and mussels.

These strange black lumps always remind me of armoured cars. This is mainly a very southerly species which is found widely around exposed Cornish coasts, but it has been recorded as far north as the Farne Islands and Scotland.

Celtic sea slugs may not be the most classically pretty slugs, but they are incredible animals. They are able to survive on these rough shores in terrifying conditions and they don’t even have gills. They breathe air and hide away in cracks in the rock when the tide comes in, staying alive by keeping an air pocket sealed inside their bodies and breathing through their skin when needed.

If there is one Celtic sea slug, there is usually a whole colony and we found dozens more on the rocks all along the gully.

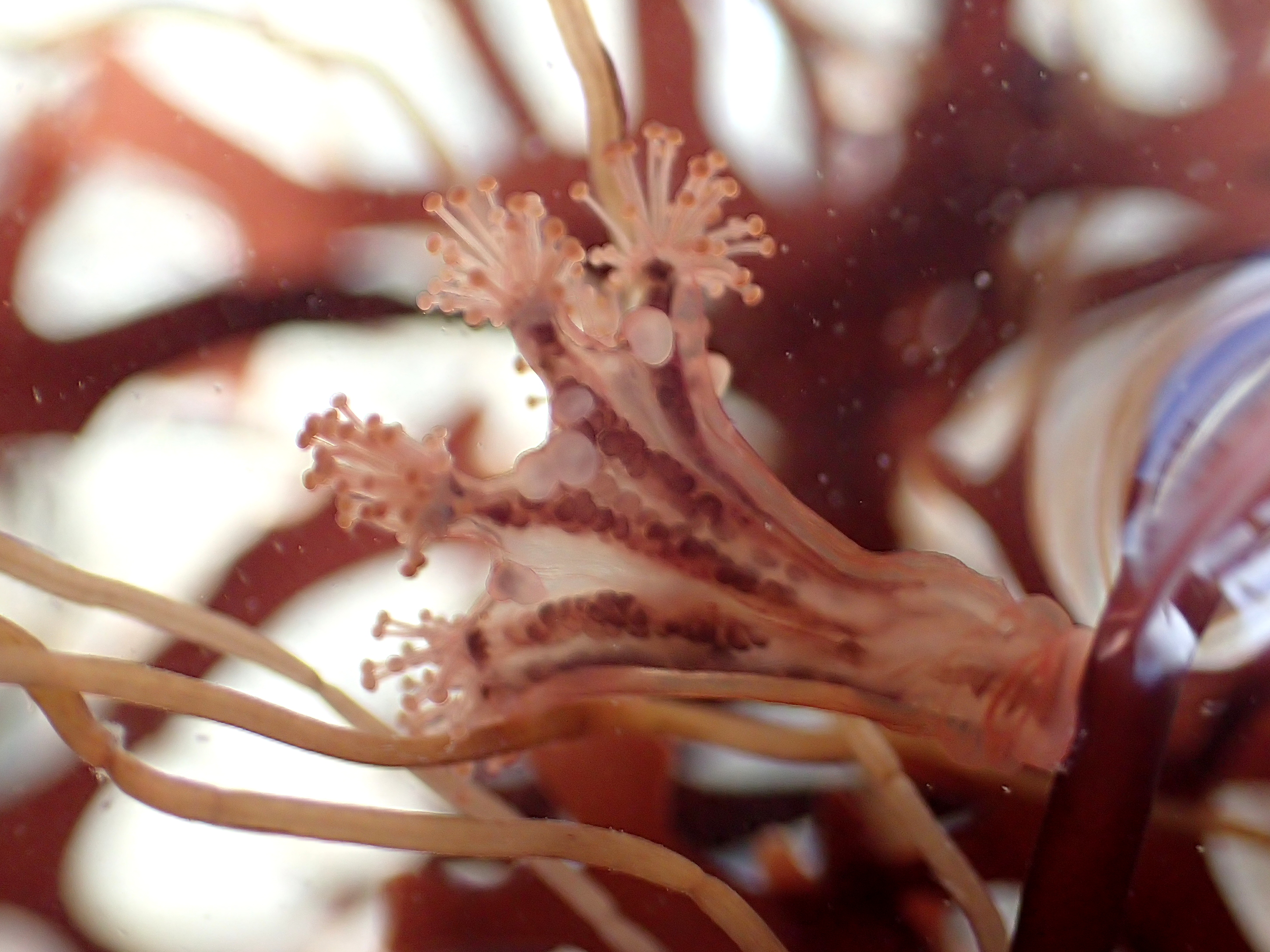

Our next stop was a deep overhang with a pool at its base where we knew we would be able tick off another species from our bingo card, the scarlet and gold cup coral.

We had to kneel and lie at strange angles on rocks encrusted with sharp barnacles, but we were soon rewarded with the brilliant glow of many corals.

These tiny orange and yellow corals open their transluscent tentacles in the water here and always astound me. Their delicate soft bodies encase a spongy, fragile exoskeleton, none of which looks like it could stand up to a gust of wind, let alone the fierce, pounding seas that rage through this gully on a daily basis. Despite their soft appearance, scarlet and gold cup corals, like the Celtic sea slugs, thrive in these wild places.

It was a good thing we had left ourselves plenty of time to explore this rock pooler’s paradise. Between deep pools packed with enormous snakelocks anemones and prawns as big as my hand, we scrambled and stared at the huge diversity of species in front of us. Arctic and three-spot cowries moved across the damp surfaces encrusted with pink seaweeds and colourful sea squirts. Groups of light-bulb sea squirts seemed to shine out from the dark water and so much life abounded on every surface that we moved with great caution for fear of accidentally treading on creatures.

The underside of a large boulder at the head of the gully was coated in a red sponge. A quick inspection revealed a small white coil of sea slug sponge. It took me longer to find the slug, which matched its background flawlessly. Rostanga rubra are a common find on these sponges but this was another first for my friend who is almost as obsessed with slugs as I am. He was so delighted with this little find that he took some persuading to move away from the gully before the tide turned.

On our way out of the gully, we waded through a pool, up to our waists in the water and no longer caring how wet we were. Hidden at the back of the pool we discovered a deep hole in the rock that harboured dozens of scarlet and gold cup corals and many large snakelocks anemones. I spotted a leg sticking out from underneath this one and uncovered this Leach’s spider crab (Inachus phalangium) sheltering there.

A shallow pool nearby was dotted with tufts of rainbow weed. To our surprise, these harboured many Asterina phylactica – a small species of starfish. A nearby clump of codium seaweed was also home to several Elysia viridis sea slugs.

On our way back across the beach, my friend found a clump of seaweed with half a dozen stalked jellyfish growing on it. This time, the blobs of the primary tentacles between the arms were easy to spot and we could be sure that these were Haliclystus octoradiatus.

With most of our bingo card of southerly species complete and with another day of rock pooling to try to find the remaining species, my friend set off up the beach to rest and enjoy a well-earned picnic.

Junior and I lingered in the sunny pools, exploring further into the slippery masses of thong weed and kelp until the tide turned.

To celebrate the rare August sunshine, we finished the day with a visit to the vast rock pool where I used to swim as a child. Plunging into the cool waters, I experienced the familiar feelings of wonder and trepidation at the thought of what might lurk in the depths.

We splashed and floated between the rocky walls, finding starfish, prawns, star ascidians and sponges as we swam, side by side. Time might move on, but this beach never loses its magic.